Biography

« My way of life, my very being is based on images capable of engraving themselves indelibly in our inner soul’s eye. »

Self-Portrait, Age 15 © Louis Stettner Estate

« My way of life, my very being is based on images capable of engraving themselves indelibly in our inner soul’s eye. » With these words Louis Stettner, celebrated photographer of the twentieth century, described a passion for photography spanning seventy years.

Louis Stettner (1922-2016) was thirteen when the gift of a box camera from his parents planted the seeds of his long career. Soon after, an article by Paul Outerbridge Jr. in a camera magazine helped the young artist appreciate the great potential of photography for interpreting the world around us.

Throughout his teenage years, he made regular Saturday visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where he persistently worked his way through the complete history of American photography by studying original prints and back issues of Camera Work. In the course of this independent study he was particularly moved by the works of Alfred Steiglitz, Clarence H. White and Paul Strand. Visits to Stieglitz’s gallery American Place also informed his early development. Later in his teens, Stettner contacted Paul Strand to critique his own work and thus began a relationship that was to resume and deepen in 1951 in Paris.

In his late teens Stettner took his first and only classes in photography, given by the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers devoted to a newly developing socially conscious photography. Through the Photo League’s exhibits, Stettner was further exposed to the work of Weegee, Edward Weston, and Lewis Hine.

In 1942, at the age of nineteen, Stettner enlisted in the army in the Signal Corp, having requested to be trained as a combat photographer. Stettner was initially sent as a military student engineer to Princeton University before eventually being posted as a combat photographer to the Pacific and eventually to Hiroshima.

Self-Portrait, In the Army, ca. 1943 © Louis Stettner Estate

The experience of participating in World War II was to profoundly permeate Stettner’s life-long development as a photographer:

« If my photographs have always been embedded in daily life, with the emphasis on what is called the ‘common man’, it is because my early formative years were deeply politicized by world events. I grew up with the rise of totalitarianism and what was part of a hurried transformation of the average citizen into a soldier… »

« It is hard to assess what taking battle pictures has meant to me as a photographer. I do know that I lived and fought together with my fellow countrymen – fishermen, industrial workers, storekeepers – whom I had only brushed up against in Times Square… Farmer boys from Kentucky hills… How they successfully fought against fascism has given me a faith in human beings that has never left me. »

After his discharge from the army in December of 1945, Stettner returned to New York and resumed his association with the Photo League. Sid Grossman, a revered teacher and photographer with a deep faith in the creative potential of people and in their ability to solve critical problems, befriended Stettner and was to become a decisive influence. He went on to appoint Stettner, twenty-two years old, a teacher at the League. It was at this time Stettner first met Weegee, a prelude to their long-term friendship.

Of his experience in the Photo League, Stettner was to later write: « The League taught me that no matter how original and talented the photographer’s vision might be, the ultimate success of the photograph was mutually dependent on the photographer and world of reality around him… not to ignore, but on the contrary, to concentrate his talents on everyday working people and what was immediately around him in terms of living and environment. »

Self-Portrait, ca. 1950 © Louis Stettner Estate

In 1947, Stettner left on a three-week trip to Paris which extended into five years. In Paris Stettner received a commission from the Photo League to gather prints from significant French photographers (Brassai, Izis, Boubat, Doisneau, Ronis, Masclet, etc.) and organized the first exhibition of post-war French photography in the United States at the Photo League’s gallery (1948). The experience of selecting these photographs was the beginning of several vital friendships with fellow photographers, foremost Brassai, whom Stettner considered as his master and with whom Stettner maintained a close friendship for decades. His lifelong friendship with Edouard Boubat also begun at this time. Stettner also explored during this time his interest in sculpture studying with Ossip Zadkine at his Paris studio.

Stettner thus became an active and valued member of the post-war photography scene in Paris, where he would be visited by the likes of Eugene Smith and Robert Frank on their trips to France for discourse on his work. Paul Strand’s return to Paris permitted Stettner and Strand to establish a routine of weekly lunches. In 1950, Stettner was a major prize-winner in LIFE’s Young Photographers contest.

On Broadway, Midtown, 1985 © Louis Stettner Estate

Stettner returned to New York in the early 1950s and worked as a freelance photographer for LIFE, Time, Fortune, Paris-Match, etc. as well as advertising firms in the US and Europe. This resulted in his traveling between the two continents. Early on he also photographed for the Marshall Plan but was to lose his job for his previous association with the Photo League and for refusing to reveal the political views of his fellow Photo League members to the FBI. During the later fifties, Stettner, continuing to pursue his personal creative photography begun in Paris, completed his iconic group of series, Penn Station, Nancy, the Beat Generation, and Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen.

It was also during this time that Stettner, possessing a sense of social and economic justice, a keen eye, and a vast self-taught knowledge of both the technique and history of photography, first began to write about photography. This was a pursuit that he was to continue periodically over the next forty years. Beginning with 35mm Photography, History of the Nude in American Photography, and later followed by his noteworthy 1970s column, Speaking Out, of Camera 35, Stettner was one of the rare photographers of the twentieth century who critiqued the historical development of photography during his time from the point of view of a working photographer.

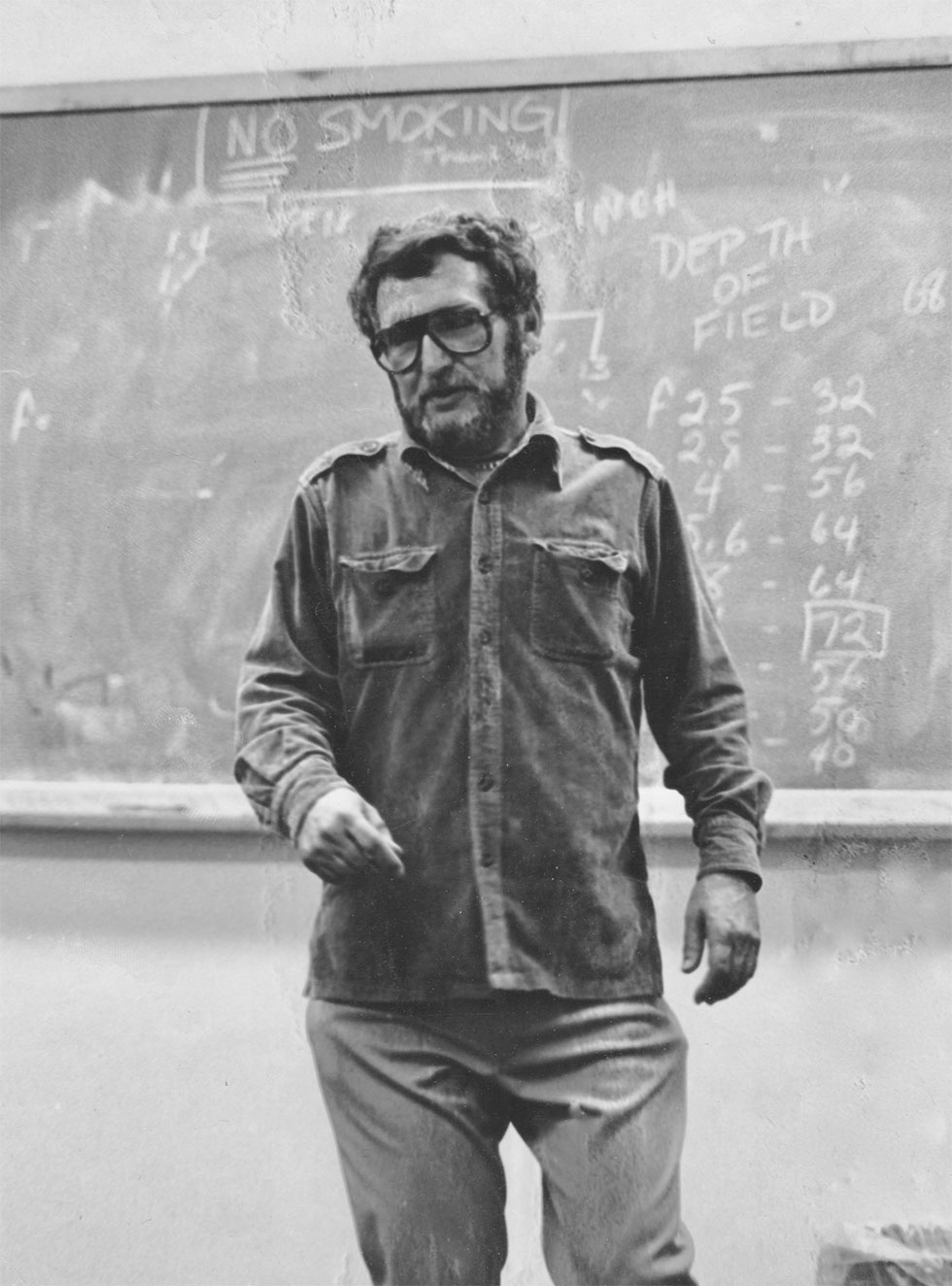

Teaching Photography at CW Post, Long Island University, ca. 1975

Louis Stettner, 2016 © Samuel Kirszenbaum

At the end of the 1960s Stettner began teaching and lecturing at Cooper Union, Brooklyn College, then at Long Island University. Having been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts grant, Stettner photographed his Worker Series. In 1975, he was awarded First Prize at the Pravda World Contest for Photography and spent six weeks photographing the Soviet Union.

By the early 1980s Stettner had ceased both teaching and writing his Speaking Out column, devoting the next several decades to furthering the development and expression of his own creative vision.

In 1990, Stettner returned permanently to France, where his photographs continued to be appreciated throughout Europe. He also began to paint, draw and sculpt. He was awarded the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 2001. Notably during these last years, Stettner began his Manhattan Pastorale color series through summer trips to New York and a three-year project of photographing the Alpilles in Provence with an 8×10 large format field camera, continuing as ever to print his own photographs. Stettner died in Paris on October 13, 2016, a month after the closing of his exhibition, Ici Ailleurs, at Centre Pompidou.

Throughout his prolific career, Louis Stettner, a force of nature with a Whitmaneque passion for life and the inquiring mind of a philosopher, interacted with and was befriended by many of the most significant photographers of the Humanist school of photography of the 20th Century: Stieglitz, Brassai, Strand, Weegee, Cartier-Bresson, Sid Grossman, Lou Faurer, Lisette Model, Boubat, among many others. The encouragement of fellow photographers, whose reflections and critiques of his work Stettner profoundly valued, was to reinforce a life-time passion, that of grasping the significance of life and reality around him.

« …it was a joyous route, such magnificent sights and human splendor along the way that difficulties magically effaced themselves. One regretted nothing and would have it no other way. »

Louis Stetter, Wisdom Cries Out in the Streets