Writings

Reflections on SPEAKING OUT

From Wisdom Cries Out in the Streets,* — 1999

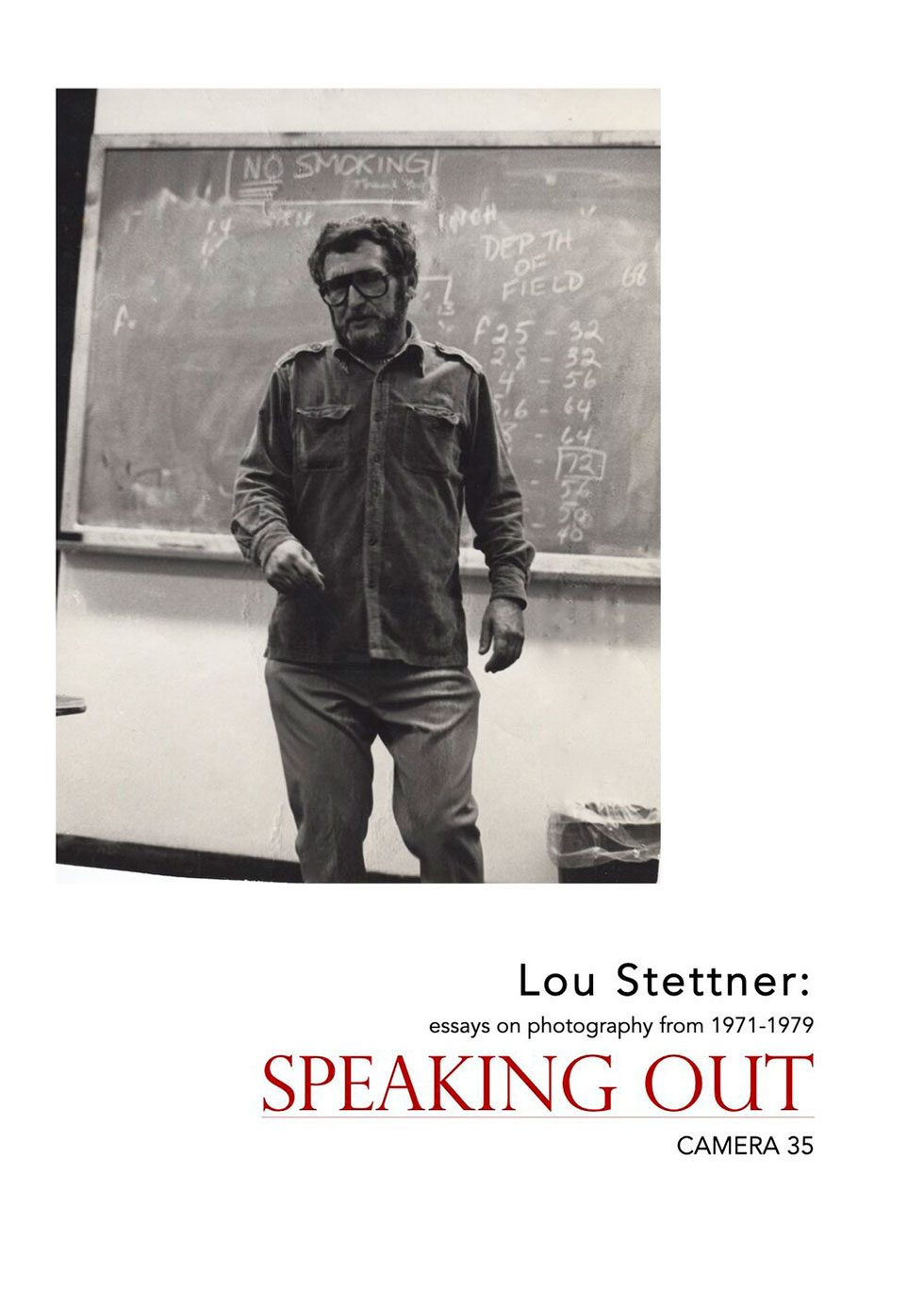

These essays [Speaking Out] are chosen from a monthly feature I wrote for Camera 35 (1971-79), first entitled “Speaking Out,” and then “A Humanist View.” Looking back after so many years, I naturally see some things I would change or develop more fully to embellish my thoughts and feelings about photography. Such tampering, however, compromises the freshness of what I originally wrote. As first published, they reveal quite faithfully how I felt at the time and also offer a good reflection on the crosscurrents of photography in the seventies. There are some issues I have to comment on. It was always very difficult for me to simultaneously be a photographer and a critic of my fellow photographers. Expressing appreciation was no problem, but I am afraid that when I differed with the approach of fellow photographers, I was often too vehement in defending my point of view-just as an Impressionist painter might, in the heat of debate, angrily denigrate the values of the classical school of painting. I was also being unfair at times in asking that their work have a political conscience when such purpose was simply not an integral part of their vision or what they were trying to do. I see now that I may have mistakenly made their work seem diminished by pointing to an absence while they may have been expressing other presences. I therefore sincerely apologize here for not having given enough credit to the many qualities that their photographs possessed.

I also made a serious error when dealing with the “establishment” by considering it a monolithic block. Very often, enlightened curators convinced of the truth, passionately and courageously carried out policies that were against the best interests of institutional culture. In looking over “Make’m Indestructible,” which was more or less my credo at the time, the essay seems uncomfortably close to a clearly defined formula for creative photography. I now feel that there are more complex influences involved in taking photographs. There is so much that cannot be fully explained; we simply have to accept the element of mystery as being an integral part of the image. I would even say that if you know very clearly beforehand, before even picking up the camera, how the photograph is going to turn out, you may be on the wrong path.

Finally, these essays were not meant to be a collection of sober, carefully measured opinions. They were more in the nature of an impetuous diatribe, a lusty speaking out. I was not necessarily trying to convince, but rather to clarify how I felt about photography and life, which I saw as uniquely one.

Louis Stettner

*Wisdom Cries Out in the Streets, Publisher: Flammarion, Paris, 1999

WEEGEE: THE QUINTESSENTIAL NIGHT WORKER

Lou Stettner — February, 1978

Weegee was an authentic New Yorker. He had been a violinist, busboy, day laborer, candy peddler, movie actor, lecturer, darkroom technician, and photographer. During the many years of our friendship I saw him as a ribald clown, a gutteral egomaniac, a bawdy sensualist, a shy, silent observer of murder, and a passionate humanist. He was often described as a rather portly, cigar-smoking, irregularly shaven man who slept in his clothes—and looked as if he had.

Weegee came to New York at the age of 10 in 1909, a member of a large emigrant family from Austria. The family settled in the gut-rock bottom on the Lower East Side. Weegee became part of Manhattan’s working poor; he was forced to leave school at the age of 14 (in spite of the principal’s pleading with him to stay) because his family badly needed the extra income.

Many of Weegee’s most important photographs were taken in this same ghetto, and, to his credit, he never sentimentalized or romanticized life there.

With the success of his first book, Naked City (1946), a legend quickly formed around the Lower East Side boy who “made it,” shedding a kind of glamour upon this period of his life. Actually, his slum childhood and early working days, as candy peddler and busboy at the automat, represented a ferociously bitter struggle to survive, the scars of which seriously interfered with his later development as a photographer.

Weegee left nothing about himself to chance. Every bright adage or off-the-cuff wisecrack came from a barrel of tangy sayings, carefully culled, flavored, and saved for the right occasion.

Weegee was always busy creating Weegee, constantly in the midst of a long campaign of self-improvement, engineering a bigger and better Weegee, trying to force the world not only to sit up and take notice but to lean over backward in praise as well. After a series of odd jobs (including a short stint in a commercial photo studio), drifting in and out of dire poverty, he finally managed to land a permanent position as the darkroom man at Acme News Services. He was almost 24 years old and he worked there for the next 12 years.

Without Weegee’s realizing it, his being cooped up in a darkroom for more than a decade was really the genesis of the major achievement of his life, his book Naked City, and of the pictures he was to take as a news photographer.

“Over the developing trays in the darkroom at Acme, history passed through my hands. Fires, explosions, railroad wrecks, ship collisions, prohibition gang wars, murders, kings, presidents, everybody famous and everything exciting that turned up in the Twenties. I handled the first flashbulb, produced by General Electric to take the place of the dangerous and messy flash powder. I saw the first photograph of President Coolidge transmitted over telephone wires from the White House to New York City; I processed it. Photography was growing up, and so was I.”

Weegee was dealing with what is euphemistically called “news”: an event that has significance for a large number of people. Weegee discovered later, as a free-lance news photographer, what it was that the public was actually interested in seeing. His photographs of murdered gangsters sold because, he felt, “It was during the Depression, and people could forget their own troubles by reading about others’.” In addition, he found out that what they wanted varied from year to year and that different newspapers appealed to different classes of people. No matter how journalistic taste changed, he was always dealing with dramatic events aimed at a mass audience, and functioning as an artist without knowing it.

In 1935, Weegee quit his darkroom job and became a self-declared freelance photographer. It was a radical, brave step, considering his past and the good salary (50 dollars a week) he had been earning for those Depression days. He rapidly acquired, within the first year of free-lancing, a technical mastery of picture taking, which completed the training begun in the Acme darkroom. With practice he came to know all the characteristics of his press camera, the light of his flashbulbs and the moment and angle of view that would best reveal his subject. He used all these elements to communicate visually his heartfelt reactions to the life around him.

For the next 10 years, until the publication of Naked City in 1946, Weegee was a New York free-lance news photographer. That was his true profession, and for the rest of his life, in talk, dress, and manner, he was one. In fact, there was an alarming resemblance between Weegee and the classic Hollywood stereotype of a press photographer. He smoked cigars, wore a crumpled fedora, and, like all press photographers, knew when brashly to put his foot in the door. He specialized in night work (when the salaried staff photographers for the newspapers were sleeping) and dealt mostly with fire, crime, and mayhem. He established himself and got to know what photographs the various newspapers and news syndicates were likely to buy.

“I found out that life was like a time-table. Between twelve and one o’clock, you had the peeping Toms outside of nurses’ homes. For peeping Toms the cops didn’t even bother. From one to two you got stick-ups, especially at delicatessens. From two to three—oh, well designate for auto accidents and fires. Four o’clock when the bars closed, we had trouble. A lot of the boys go to a nice comfortable bar, away from their nagging wives, and really have a good time. Four o’clock means frigid air—they don’t want to go home, just because the guy’s got to close up. So the boys in blue arrive and very gently get them to go home. At about five o’clock is the time for tragic things! Many people stay up—stay up all night. Ill health, financial trouble, affairs of the heart keep them up all night. They brood—they think—they try to go to sleep. About five or six o’clock, when the dawn breaks, they’re at their lowest physical state. It is then that they take a dive out of the window. I tried not to cover that. After all these stories that I covered—a murder a night for 10 years—the sight of a cut finger or anything like that makes me sick! A murder I didn’t actually see. I was in a daze. An interesting thing about when a woman jumps out of a window, nature is usually very kind. When she lands on the street there won’t be a mark on her face. If she had her shoes on—one shoe will usually come off.”

Starting in 1940, Weegee worked for PM, a progressive evening newspaper, on a weekly retainer for several years. PM gave him great freedom and let him choose his own stories. He produced his most significant body of work during this period.

New York City was Weegee’s great theme. He was never to succeed as well with his camera elsewhere. But there is much more than Weegee’s love of the city and his conception of beauty. Weegee dealt with people under unbelievable stress. The late ’30s and early ’40s brought Murder, Inc., and the bloody gang wars to New York. Besides shootings, there were also the fires, stabbings, muggings, and robberies. Weegee earned his nickname, derived from Ouija board, because he often seemed to know beforehand where the scene of the crime would be. Through it all, he was a profound humanist and a compassionate observer of human beings, portraying them as innately tough, with the strength not only to survive but to flourish.

The ex-darkroom man of 1935 was very different from the Weegee of 1939, who had spent a thousand and one nights experiencing and getting to know New York intimately. Nor was it just crime that he covered. He came to have a Rabelaisian love of celebrations, parties, people having a good time: bars, Village dances, New Year’s Eve balls. He believed that people were capable of enduring anything. He had faith in their capacity to suffer and enjoy. The horrors that he saw as a news photographer could have crushed him; instead, they made him all the stronger.

He never consciously understood the aesthetic reasons that made some of his photographs, like The Critic, great. Often he had an undue fondness for mediocre photographs. The same photograph would sometimes be printed and cropped in three or four different ways, as if he was unsure which one worked best structurally.

Finding a publisher for Naked City took more than two years. Weegee was rejected by almost every publishing house in New York. Then Naked City went almost immediately into three printings, and Weegee became famous. He also became a celebrity, even fashionable. During the brief time he was in fashion, he was presented as a camera-toting Damon Runyon character. After Naked City to the end of his life, most of his creative energies were to be wasted in pursuing one big-money scheme or another. He insisted on turning public esteem into notoriety, mercilessly exploiting his own reputation by playing the cigar-smoking, wise-cracking buffoon.

The critics did not take kindly to Weegee’s “trick” period, perhaps justifiably. He camouflaged his good manipulations with so much commercial banality and facetiousness that they were hard to evaluate and even harder to take seriously. There was also, unfortunately, a critical tendency to classify him rigidly as a fire and crime photographer: the critics seemed reluctant to give him one more dimension, grant him one more valid direction of growth. Yet Weegee’s photographic career did not entirely stop with his newspaper work.

Certainly his manipulated images do not match in importance his Naked City accomplishments as a news photographer. He did not realize that for every manipulation he had to pay the price of contrived artificiality. If we look over his life in perspective, however, we see that what is most vital in his manipulations does have a meaning. The satire and the childlike fantasy seem almost vitally needed antidotes to the overdose of suffering and violence he witnessed and interpreted for us for more than one intense decade.

It has become clear that Weegee’s photographs captured and interpreted what was most vital in the contemporary scene. He confronted great brutality and affirmed our ability to withstand it. He confirmed, over and over again in his photographs, his own belief in humanity and a basic optimism that he felt would carry us through.

(from the introduction to WEEGEE. Introduction © Louis Stettner 1977

© 1977 by Wilma Wilcox. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1977.)

LEWIS HINES: HOMMAGE TO HINES

Lou Stettner — June, 1976

“No greater mistake could be made than to assume that Hine was strictly objective toward his subject matter.”

The photographic accomplishments of Lewis Hine (1874-1940) is our most vivid proof in American photography that pictures can have strong social and political dimensions without taking away from their aesthetic importance. Indeed, the social and political aspects of his photographs are not only inseparable from their artistic achievements, but greatly contribute to their originality. As it has been pointed out, “new human experience breaks old patterns of artistic ways of seeing.” Here I can only use the word “tremendous” to describe the human experience that Hine dealt with for more than 30 years. Starting with Ellis Island in 1905, he photographed the great wave of immigrant labor that came to this country; for the next three decades he documented throughout the land their new way of life and work here. They were part of his great subject matter: the American working people in factories, construction sites, doing piece work at home and especially in mines (Hine particularly loved miners, saying of them, “other workers are just as human, but so much less wonderful”).

No greater mistake could be made than to assume that Hine was strictly objective toward his subject matter. In the introduction to his book Men at Work, he clearly states, “I have toiled in many industries and associated with thousands of workers. I have brought some of them here to meet you. Some of them are heroes, all of them persons it is a privilege to know.” That’s quite a recommendation! Hine, originally trained as a sociologist (with a degree from Columbia), taught elementary school and then quickly turned to photography, making a photographic social study of working people his life’s work. Not only did he find the living and working conditions of workers in the first part of the 20th Century truly horrible, but deeply felt it as a human being.

He wrote in 1914, after seven years of photographing children at work, “Tenement homework seems to me one of the most iniquitous phases of child slavery that we have. It is then that I come nearest to hysterics. And so, if I seem to be smiling over the subject at any time . .. you may rest assured I would rather weep.” Politically, he had hoped his photographs would cause the swift enactment of laws against child labor. Instead, it took a painfully long time.

Very often, Hine is described as a stoic, shy man, with no real anger in him against the super-exploitation of the human condition he was dealing with. Not so. As Judith Mara Gutman points out, “His anger grew as the Captains of Industry found new tasks for the tots to try.” Hine wrote, “Did I say tasks? Not so—they are ‘opportunities’ for the child and the family to enlist in the service of industry and humanity. In unselfish devotion to their homework vocation, they relieve the over burdened manufacturer, help him pay his rent, supply his equipment, take care of his rush and slack seasons, and help him to keep down his wage scale. Isn’t it better anyway for everyone to be working instead of expecting father to do it all?” This is not just anger but an anguished mixture of sarcasm and despair, a deep hatred of the hypocrisy of the factory owners. Curiously enough, this spirit of revolt was never to express itself directly in his photographs. He is certainly not a Daumier with the camera. As far as I know, he never photographed militant workers on strike or in struggle. He lived through an epoch that saw an heroic and successful fight waged by the workers themselves for the first eight-hour day, unemployment benefits, social security, safety conditions, etc. Somehow Hine never took part in these battles.

His inability to visualize the worker as a dynamic human being capable of fighting for and bettering his human condition, is perhaps his one great weakness as a photographer of the working class. Yet, through the lifetime span of Hine’s photographic production, one sees a definite pattern of growing confidence in the strength and ability of working people. Starting in 1905 with his Ellis Island series and followed by his many years of work for the National Child Labor Committee, Hine concentrated on the martyrdom of a people living under unbelievably oppressive conditions: breaker boys (seven to 12 years of age) sorting coal in dust-choking bins for 12 hours at a time; crippled children (often missing a limb from accidents in the factory) hanging out in the streets; crowded tenement slums with whole families (including four-year-old children) doing piece work around the table; unemployed or old people, the flotsam of society, freezing on street corners or on breadlines. He did not photograph them in strident, shrill terms. There is a stoicism, almost as if the great and endless patience of working people has somehow been transmitted to Hine himself. Yet, they are photographed by Hine with great dignity and nobility, as if Hine realizes that their life work (they are actually building America) gives them heroic qualities. He sees them, in spite of all difficulties, as self-assured and devoid of all self-pity. He also sees working people, in spite of their intense exploitation, as being aware of the joy and satisfaction productive labor can give the one performing it.

Hine over the years was to pass from his chronicling of the super-exploited to a documentation of grown-up workers at their everyday tasks. This later period was to be epitomized in his great picture series of the Empire State Building being built. It is, in essence, a paean of praise to the skill, courage and organizational ability of workers. He was to eloquently write in the preface to his book Men at Work, “I will take you behind the scenes of modern history where … the character of the men is being put into the motors, the airplanes, the dynamos upon which the life and happiness of millions of us depend is to be found.” We seethe “skyboys” as Hine called the steeple jacks, doing trapeze acts with iron girders in the clouds. They are no longer portrayed as helpless or forlorn, but smiling gods building great cities in the sky. There is a majestic calmness, a quiet confidence in these later photographs of workers, as if Hine had come to realize that they were the real masters, not the bosses.

His Men at Work, published in 1923, is a prophetic book. The pitiful shoe shine boys and street urchins sleeping in the alleys have grown up to be men of authority and courage. Hine praises their skill, fortitude and perseverance. In all of these photographs, they are never enslaved by the machines but are the masters of them. The last photograph in the book is of a little worker happily smiling, his round glasses glinting in the sun, almost like a proleterian puck enjoying the knowledge of the importance of his class. Hine also said it verbally: “The more you see of modern machines, the more may you, too, respect the men who make them and manipulate them.”

Hine gave a lifetime commitment to his work. Not only did he cover the New York tenement slums; his task was to take him south to paper mills and a coverage of working conditions and factories in rural America. During World War I, he photographed the plight of a working population caught up in the debacle of a savage upheaval in Europe, which he covered as a photographer for the American Red Cross.

No less interesting, are the aesthetics of Hine’s photography. Certainly, he was not native or primitive with the camera, for he started out with training in wood sculpture and had a very lucid concept of the camera’s artistic possibilities. He could state very simply and wisely, “Good photography is a question of art.” The stamp on the back of his photographs read “Interpretive Photography,” by which he meant to emphasize that the photographer was not merely recording reality. He had a highly developed sense of structure in a photograph, realizing that the specific angle of view could eliminate or play down non-essentials and strengthen the more important visual elements. He stated very clearly, “It is especially necessary from the start, to realize that every photo should be a study in relative values—that the important things are to be emphasized while the unpleasant and non-essential are to be minimized.” He saw the process of distillation necessary in making a good photograph as strengthening a sense of reality! He wrote, “Whether it be a painting or photograph, the picture is a symbol that brings one immediately into close touch with reality. In fact, it is often more effective than the reality would have been, because in the picture, the non-essential and conflicting interests have been eliminated.”

Hine s photographs can appear deceptively simple. They often misleadingly look like modest documents. Yet his best ones (apart from the commercial bread-and-butter assignments that were outside his field of interest) are highly organized and structured. Foreground and background “work” together are genuinely felt in a visual way. We must also bear in mind that the primitive equipment he worked with placed limitations as to what he could do in terms of action and depth of field. His photographs are not bold in design, but quietly, almost effortlessly structured, so that often we feel at ease with working people, as if we had known them a long time.

Elizabeth McClausland was perhaps the first to point out the historical significance of Hine’s work. There is no disputing the fact that, if with time his photographs take on an ever increasing importance and popularity, it is because they give us in a most pertinent and creative way a feeling and sense of an important part of our history. Not only does he fill us in on what was not previously known, but he also historically informs us what a previous generation suffered to give us our present society as we know it. Disturbingly enough, it is the very brutal truthfulness of Hine’s work that even today, prevents its wider dissemination and publication. An adequate complete monograph has yet to be published and a thorough one-man show to be organized.

The importance of Hine’s work is not only historical. In the last analysis, it was Hine’s personal vision of working people, his tender interpretation of their dignity, courage and many human qualities, that makes his work endure. For as far back as Ellis Island when the immigrant was often looked upon in the popular press as a “dirty greenhorn,” Hine portrayed them for us and for history as solemn and dignified carriers of a sophisticated, rich and varied cultures from the Old World. He does not scorn but almost seems to caress visually their embroidery and regional dress. He saw their ethnic differences as enriching America, not depriving it of anything. Which makes Hine today the most modern of moderns.

CARTIER-BRESSON: MERELY MORTAL

Lou Stettner — April, 1975

“The photograph tells us all about the photographer. Cartier-Bresson’s people are always slightly smaller, never bigger than life.’’

Hardly anyone these days would be foolish enough to deny the mammoth importance of Henry Cartier-Bresson in the contemporary photographic scene. To squarely deal with him is another matter. All too often the tendency is to categorize, label and tuck him away as a great master of photography. But his accomplishments are not dead vestiges, so-called “beautiful photographs,” isolated from the influences of time. On the contrary. Bresson’s influence runs like a giant artery all through creative photography in the 70’s.

His great contribution is an almost single-handed discovery of the aesthetic potential of the 35mm camera. He has amply demonstrated and expounded upon the small camera’s possibilities in a veritable cascade of photographs, both published and exhibited. What’s more, with a rare intellectual precision and verve, he has brilliantly articulated his credo in words. I cannot cut out a word from the following paragraphs by him. They are a compact but monumental thesis on the creative use of the modern hand-held camera:

“To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.

“I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us, which can mold us, but which can also be affected by us. A balance must be established between these two worlds—the one inside us and the one outside us. As a result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come to form a single one. And it is this world that we must communicate.

“But this takes care only of the con¬ tent of the picture. For me, content can¬ not be separated from form. By form, I mean a rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines, and values. It is in this organization alone that our conceptions and emotions become concrete and communicable. In photography, visual organization can stem only from a developed instinct.”

Hardly a working photographer today (myself included) has not benefited from his discoveries and accomplishments. He is very much a part of our cultural heritage in photography, and his influence leaps right on into the present. As a photographer, he has always insisted on an approach that many photographers today, unfortunately, ignore.

He practices a strict self-discipline, an almost obsessive insistence on perfection that is the essence of all great art. Just as a great violinist tries not to be just the tiniest fraction of a second off timing, so does Cartier-Bresson insist on a “rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines and values.” This means rejecting—forgetting about or tearing up our near misses—pictures that have qualities but didn’t quite make it.

His pictures are also very French in flavor and tradition. By this I mean a savouring of the human anecdote (wed¬ dings, street quarrels, lovers interacting); an almost sensuous pleasure in textures, shapes, light tonalities and movement; a keen eye for the dramatic (Buchenwald guard on trail); and the use of satire and irony (huge industrial derricks behind sunbathers, an old woman wrapped in a flag). We can also see in his work the happy influences of Delacroix and Daumier. Above all, he has a great appreciation for and understanding of other artists. His portraits, ranging from Sartre to Matisse, rank among his major accomplishments.

I would have liked to end here. Most unfortunately, Cartier-Bresson also has within him a negative tendency that is the spiritual blight for artists of our time. In the last three decades, it has almost completely dominated all of his later work; he, too, takes the ideological position that the artist is an objective observer, someone who has the distinction of being apart from and above the action, strife and turmoil of the world. This attitude, of course, is seen in his work.

The photograph tells us all about the photographer. Cartier-Bresson’s people are always slightly smaller, never bigger than life. He has a tendency to see them as pawns, rather like marionettes in the hands of destiny (or the photographer). There is barely warmth, much less great compassion for or a passionate conception of people here. We are far from the humanist concept that credits human beings with great potential and dignity. Cartier-Bresson is analytical and removed. He has taken, to put it bluntly, an elitist position.

All through his later work, including his books Man and Machine and France, as well as his latest exhibit, “Apropos SSR,” at the International Center of Photography, we sense his alienation, is withdrawal onto a pedestal. He becomes the God Seer with a camera, instead of one human being trying to understand and feel for other human beings and the world around him. Most of his later works (we still have about a dozen masterpieces among them) are ambiguous, often displaying a mystical obtuseness that comes about when the photographer is not relating in the most vital way to reality. They make all the more powerful his great series taken in the Spanish slums in the 1930’s when Cartier-Bresson, the man, and his photographs were ennobled by his compassion as well as his insight.

However, his negative tendency has always been part of a complex contradictory process within himself. On the one hand, he splendidly states, “I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world round us . . while he also claims, What I am trying to do more than anything else is to observe life.”

First, he points out the intimate amalgam between the photographer and the world around him, which are both passing through an “act of living”; then he denies it as he becomes the observer. The “significant event,” from Shakespeare to Cartier-Bresson, is the artist committing his feelings and understanding of the world. Looking for the “decisive moment” alone is playing with forms and shapes for their own sake, which is exactly what has happened to Cartier-Bresson.

From his exhibit, “Apropos USSR” (a careful study of it failed to tell me how he felt about the country), I have chosen two photographs to illustrate the two directions in Cartier-Bresson’s work.

In “Worker speaking to foreman” (they are discussing a problem in the shop), we have all of his sophisticated, yet powerful grasp of form to bring out the significance of an event. The face-to-face encounter, almost brutal in its visual intensity, is subtly softened by the second woman, who is a pivotal focal point be¬ tween the two co-antagonists. The black¬ ness of the shop tonally dramatizes their confrontation. Really, it is only a simple exchange of ideas, perhaps about a minor problem, but Cartier-Bresson, in a feeling way, reveals to us the surprising personality exchanges ‘involved in production. The worker is almost super¬ masculine, with his muscles and big wrench, yet he is speaking on an equal level to a woman in skirts who has more authority.

In “Picnic with Automobile” (my own title), we have, epitomized, Cartier-Bres¬ son’s negative tendency. The people in this picture move between the automobile in the foreground and church steeples in the rear, like pathetic figures in a puppet ball. Perhaps his intention was to show conservative peasants hopelessly torn between the old and new. But the picture only succeeds in a very limited way, because Bresson is primarily preoccupied with form. We sense that he feels very much removed from these people. The picture degenerates into an exercise in visual aesthetics, a mildly interesting display of how the movement of people can affect spatial relationships when a 10mm lens’ depth of field is utilized.

Cartier-Bresson has mistakenly interpreted the aesthetics of a picture as being almost exclusively important. But a photograph is actually an act of revelation. Its real significance depends on the quality and depth of the photographer’s understanding of the picture’s content that he has been able to communicate to us (expressed visually, of course) in the most passionate and profound way.

Cartier-Bresson’s almost exclusive concern with the form and shape of this world (with emphasis on rhythm), divorced from his own understanding and feelings about life, is a downfall for us all. The photographer who considers himself a superior high priest contracted out to posterity also places a frigid distance between himself and the rest of the world. Communication becomes difficult among all concerned—the photographer, reality around him and his loving audience.

BRASSAI: THE COMET OF PARIS

Lou Stettner — December, 1973

No self-respecting Parisian Bohemian ever had time for listening to a mundane radio; so it is with some puzzlement that I distinctly remember having heard a wireless interview during my Paris salad days. The interview was with the brother of Jacques Vuillard, on the occasion of that well-known painter’s death. Inevitably, there came the question, “How would you estimate the true artistic value of your brother’s work?”

I expected a flowery eulogy, the unstinted and resounding praise usually reserved for the recently dead. “No,” the brother succinctly replied, “Only time will tell.”

I recalled this recently on the occasion of Brassai’s visit to our shores to launch both a portfolio of his photographs being distributed by Witkin-Berley and a retrospective exhibition in Washington, D.C.

Brassai is an old friend of more than 20 years standing, one of my masters, so to speak, who taught me a great deal about photography. His positive criticism and encouragement were vital in my development as a photographer. (And I am honored to say that I am the only American photographer for whom Brassai has written an introduction to a portfolio of photographs.)

Certainly, this was the time to reevaluate his photographs, seen afresh on these shores, far removed from French culture with which they are so intimately involved. Too, I would now have the perspective that only time can give.

I was first introduced to Brassai through that rhapsodic paean of praise written by Henry Miller in which he described Brassai as the “eye of Paris,” and it was Miller who also subsequently literally introduced me to him via a letter he wrote to Brassai about me before my visit to Paris.

Miller, whose literary temperment is reflected in writing as overwhelming enthusiasm or violent opposition, portrayed Brassai as some sort of Guru of the Camera, a mystical seer whose photographs are capable of penetrating with astounding ease to the very essence of reality, whether it be that of a chicken bone or a prostitute; yet in the Milleresque depiction, Brassai became some sort of extraordinary ambulatory X-ray apparatus, busily churning out soul photographs. Miller’s essay did reveal some important aspects of Brassai’s photographs, but could certainly not be called a critical appreciation, nor can unstinting praise while ignoring the weaknesses of an artist be called constructive.

While in Paris, I visited Brassai at least once a month for many years and came to what I consider a full-bodied understanding of his work. Looking at his photographs now, I realize that the “genius” of Brassai flows from his compassionate understanding of his fellow beings and of life around him. True, he has the ability to visually express this in photographic terms, but it is the profound humanism of his vision that makes his best photographs so relevant.

Brassai himself has said, “In spite of its humble submission to reality or perhaps because of it, the photographer’s vision passes into his images unconsciously. They are no longer illuminated by the light of reality but by that of the artist.” As I have said before, “We are what we photograph,” and with Brassai, there is this extraordinary non-cleavage between the man’s philosophy and his work.

I remember one summer evening wandering a Paris street fair with Brassai. There was no question of boredom. Here was a life-phenomenon taking place; the moment was real and we were two photographers living in it. He compared it to all the other street fairs he had known and finally decided: “Yes, this was good.” Not one of the best, but certainly not so bad as to endanger the whole tradition of street carnivals as they had slowly evolved throughout the years.

There is much of the Hungarian folk art element in Brassai’s work—a celebration of the everyday joys of seeing and living, whether it be in the glowing copper pots in the “Hospice de Beaune” or in the puff of white light that we see is only a little dog on the steps of Montmartre.

All of his best photographs have a feeling of fine tapestry; a lingering enjoyment over detail and texture for their own sake; an almost reverent cherishing of the banal sights and sounds and smells of the daily world. In this respect, I think the recently-issued portfolio of 11 x14 prints has failed. Brassai’s photographs are meant to be seen large, at least 14×17 (which is the size I remember their being) so that we can enjoy the embroidery of life that Brassai sees, even in the surface of a cafe table.

Brassai also has the ability to affirm. In his photograph “Gala Soiree at Maxims” there is not the slightest hint of envy or admiration for the rich. Nor does he condemn them. Instead, he ignores them! He simply presents them as they are—ostentatious, self-conscious, uptight in their tuxedos and diamonds— and tunes into his love of spectacle (very much like Fellini’s). He truly loves the splendor of the decor, the fanfare, the gilt mirror images, the glowing tablecloths.

The fullest expression of his love for the daily visual weave and warp of this world is, I believe, in his book, Paris de Nuit. Inspired by the spectacle of a great sophisticated city at night, Brassai reverently made the lamplights glow like the jewels of a necklace and the underworld Parisians move with the meaningful light- footed destiny of minor Shakespearean characters. After all, Paris was the central inspiration for Brassai’s photographs.

Yet his admiration for this crown of French culture is also his biggest weakness as a photographer. When you unquestionably accept the stereotyped popular concepts, as Brassai has done, then embellish, caress and celebrate them to new and higher heights; when you do not penetrate the masks, and give us the driving forces beneath them, the danger is that your photographs will degenerate into academic “genre” pictures. And Brassai’s photographs, seen on exhibit again after a lapse of 20 years, do essentially give us the classical imagery of Paris. Yet such photographs as cafe prostitutes and the chunky meat porter contain the main contradiction in Brassai’s work. They are the standard types you would expect to see in Paris, but the profound humanity that he sees in these people rescues their photographs from the time-worn cliches of the age in which they lived.

For example, during the 50’s and 60’s, there was the popular concept of the cabbie as garrulous and tough, but deep down, a wise philosopher with a heart as big as a city block. Although New York has never had its Brassai, the “camp” image of a cigar-munching cabbie wearing a worn cap and a quizzical sneer would be accepted and cherished, though such a photograph taken today would be hopelessly outdated. Why? Because everyone knows that while the N.Y. cabbie had these characteristics, he was a far more complex human being than the simplified image of him. Such photographs from the 50’s would be hopelessly outdated.

This is precisely what I feel has happened to Brassai’s photographs, and I predict that in the next 30 years, they will be alternately revived and rejected (just like our nostalgia feeling for early 40’s gangster movies has resulted in their periodic revival).

Tragically, as Paris changed, Brassai’s photographic production seriously dwindled. For the last 20 years, he has practically stopped being a photographer. Again, why? I remember introducing Paul Strand to Brassai for the first time. Paul shared an appreciation for Brassai’s vision, yet felt he was not making maximum use of the full potential of the photographic medium. I believe Paul was right.

Brassai has never managed to outgrow his attachment to Paris and photograph to any extent elsewhere. I honestly do not know the explanation for Brassai’s halt in photography. I hope it is not because he has accepted Miller’s evaluation at face value, of his being a visual eyeball genius who had only to point his camera for great photographs to result, which is not true. I have always maintained, a photograph reflects what’s been put into it, which means the love, profundity and understanding that has been arrived at through honest and continuing struggle.

Perhaps we should be grateful for the greatness that does come our way and not be greedy about wanting more of it. For Brassai has given us a major body of work that will be, for all time, one of the proudest jewels in our photographic inheritance.

SID GROSSMAN: A TASTE OF HONEY

Lou Stettner — November, 1973

Fellow photographers, gather around; I am now about to reveal one of the best kept secrets in American photography. It’s about a man who either taught, influenced, affected or helped develop Charles Pratt, Harold Feinstein, Robert Frank, Leon Levenstein, Lou Bernstein, Leo Stashin, Louis Stettner, Eugene Smith, David Vestal and many other photographers. A man who helped organize and develop one of the most important photographic groups America has ever known, the group that first exhibited Weston, Weegee, Doisneau and Brassai in New York; it was the Photo League. The man was Sid Grossman.

I’ve had the privilege of personally knowing Sid, of having his friendship. He was also the first to believe in me as a photographer. Which has nothing to do with his present stature as a teacher and photographer. Time has done that. Since his death in 1955, his importance has steadily increased among the relatively small circle of photographers aware of his work; he is rapidly becoming a legend.

Sid had the rare gift—I would even call it genius—of immense empathy, a complete understanding of how a photographer grew and developed as an artist. Somehow he could intuitively grasp where each student was at, without ignoring any of their complexities or contradictions. He could sympathize with their problems, yet he also knew when giving sympathy would be wrong! When it would be better for the photographer to struggle alone.

I will also go on record as saying that Sid Grossman is the greatest teacher of photography America has so far produced. This column hasn’t enough space to go into his qualities as a photographer; a major feature and portfolio of his work in an upcoming Camera 35 will try to take care of that. I would just like to give some idea here of his contribution to the art of teaching photography.

We are very fortunate in that Charles Pratt has lovingly preserved Sid’s photographic work. Equally important, Charles has kept intact a wire recording of Sid teaching several classes. I have carefully read a transcript of it and can now say, without reservation, that this document is the most important writing on creative photography in the last forty years.

The “Grossman Dialogues” are not Sid lecturing to his pupils, but a fruitful give and take with them that have a Socratic grandeur. They not only provide a key approach to how a photographer should develop, but they also contain the marks of his profound understanding of photographic trends. Not only did he clearly evaluate what was positive and important, but he also saw inherent weaknesses and false paths that photography could take. His predictions have proved amazingly correct. Prophet, teacher, photographer, he was all of these, but not in the conventional sense.

He was the first to admit this: “I am not an instructor in any classic sense. I have studied the work of other photographers, including many hundreds of young photographers who have never been heard from, so that I have a great deal of experience and therefore I can help by discussing with you your problems and mine—but that is all. I am not an instructor who bears the responsibility for making something out of you. It would be very bad for all of us if I was going to take the attitude that I was going to form you. You must bear this responsibility.”

Young photographers today have no idea how isolated creative photographers were in the 40’s. The worst kind of pictorialism dominated publications and exhibitions. Sid Grossman not only helped provide a fertile atmosphere in which photographers could develop, but his analysis of what was most important in the relatively “new” medium, creative photography, is even more relevant today! I don’t feel we can afford to wait any longer. Following are a few excerpts from the “Grossman Dialogues”: Yolla (a student): “Maybe he needs to photograph flowers. …”

SG: “It all depends on how he approaches flowers. If you approach them as a condition of life, this may be it, but if he approaches the photography of flowers as an escape, then it may be fine as therapy, but it may very well result in not turning out to be a photographer.”

On still lifes: “The big thing that was lacking was the understanding that your photograph must represent a powerful emotional response to an object and only in that way and only if you are passionately moved with a given object will you understand the design and form in such a way that it is overwhelmingly significant —that you will be able to transform the old way of understanding things into a new way. No one creates anything new and anything good without a certain amount of passion and you do not create out of a formula.”

On symbols: “Universal qualities are revealed through the most specific approach to the most specific material. You can only tell about all barber shops through one and only if you deal with this barber shop as if it is the only one in the world.”

On money: “We all need to make enough money in order to continue our work—to share in the material and cultural wealth that is produced generally by all people and to which we feel we are making a contribution. And if we can make a real contribution of being creative photographers and get back enough money to buy all the other things, it is a real honest exchange of creative people who are selling an honest creative product in return for other products which are also honest. When you find that this does not happen, you are beaten down.”

On ego tripping: “There is a certain amount of need to use whatever work we are doing to develop a sense of our individuality—a sense of ego, a sense of accomplishment. To some extent this is quite all right. This is a very valid and a very healthy element in the kind of personalities that we are as photographers. But if we are only interested in being photographers, great photographers, because we will be recognized as important people, then it is not a very valid thing and is a rather self-defeating kind of objective.”

On success: “What is real success? This question for me in the world today is merely a question of having your work, having your value as a person who can do something in this world, accepted, recognized, used. We create a product which is merely for one or two people, but it should be accepted by hundreds, thousands, millions. In that sense we need what might be called fame —certainly in that sense called recognition.

“It is most important to you to be a person who lives and grows and to create photographic work which is the result of that kind of life…which will eventually be useful to people. That is the most important thing. If you can do that, you are successful. If you have stopped, no matter how it happens- whether you stop yourself or you become fatalistic and say you cannot do that or you produce pictures which really do not deal with your life or reality—you have failed.

“How long can you continue to be a brave guy who produces the best and have this rejected? Although I have boxes of pictures nobody wants to buy, I feel that by showing these pictures and making some sort of dent, I know that the time will come when they will be usable and I will have won. I know that I would be defeated if I said that I would have to make pictures just for myself. My pictures would be dead. Or if I stopped photographing, it would be just as bad. Or if I began to photograph in a way that is acceptable to the people who are vulgarizing the nature of photography today.

Any of these alternatives would mean for me a major defeat. This is not an idealistic attitude; it’s a realistic one.

“I feel the main purpose of a photograph is to penetrate the surface appearance of an object, to discover its greatest reality, its most significant truth. The photographer should also make the most intense personal statement as to his feelings and understanding of this object.”

The above is meant to show us what we are lacking, to whet our appetite for the eventual publication of the complete “Dialogues”. A daring publisher would only be showing us his worth by doing so.

PAUL STRAND: STRAND UNRAVELED

Lou Stettner — July, 1973

We photographers are not easily shocked, but a mild wave of panic recently hit an audience that was listening to Paul Strand during an evening dedicated to the great old master.

Paul adds a tough New York accent to his very slow, unhurried manner. One has the impression he has come to know life, to appreciate it and, what’s more, to have a great deal of faith in it. His voice emanates a tremendous assurance that has almost a therapeutic effect on the listener. Therefore, consternation was all the greater when he quietly stated that very much the same aesthetic standards applying to the other visual arts also hold true for photography!

Just imagine: shunned, treated for so many years like an inferior breed of artists, we photographers have become quite convinced that we are in a completely separate bag, a whole different thing. It’s been the medium’s very strangeness that has relegated it to the back pages of the “Art and Leisure” Section of The New York Times. And since the turn of the century, when photographers tried to imitate painting, we have been taught that photography is a separate medium.

Our mistake has been to think only of the differences and to forget how our medium is related to the rest of the arts. “No separatism!” Paul proclaims; this warning has come at an opportune time. Take a look at the typical exhibit of photographs at any fashionable New York gallery. The photography critics may approve by finding them witty, relevant, pertinent, dramatic, biting, satiric or gentle; at worst, they could be entertaining or just plain interesting. But nobody ever raises the question, “Will they endure?”

Yet this is an important question when evaluating a painting or a piece of sculpture. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Michelangelo’s sculpture have just as much life in them as the day they were made. No amount of style changes in art will render them worthless.

Nor do the similarities stop there. Photography, like the other arts, is affected by sociological, historical and philosophical influences and trends. Take Paul Strand’s photographs: hardly anywhere have I seen it mentioned that Paul works in the tradition of Humanist Realism, a movement which can also be traced back in time in the work of painters—Delacroix, Michelangelo and Giotto! I repeat, we cannot have two standards of values, one for photography and the other for the rest of the arts—that is, if we are to continue to claim that photography is one of the major arts!

Humanism refers to a type of art in which the human being—yes, our fellow man-becomes the central concern of the photographer and takes precedence over all other elements in the photograph. Delacroix, although a Romanticist, was primarily a Humanist. He experimented with the bold use of color and made other important innovations; but the feeling, the central thrust of his work, was with man and his destiny. Realism refers to a depiction of life as it is really thought to be, without idealizing. In photography, we can trace Humanist Realism right back to the early portraits of D. 0. Hill, Atget, Lewis Hine, etc.

Yet right away, there will be photographers who vigorously object to tying photography in with their inherited culture and the time in which they are working. Outraged, they declare themselves to be free individual spirits doing what they like in photography, following no “ism.” They are horrified at the thought of belonging to any school or following in the footsteps of anybody. Fine! But no photographer is free from the photographic tradition passed on to him and the world around him. How, what and where he photographs are not abstract decisions made in the abstract freedom of his mind, but the result of the photographer being in this world and very much part of it.

Take Mozart, whose genius I think no one will dispute. While he was perfectly free to do anything he liked, Mozart was forced to work with his time’s tradition of developed classical music (which he was to carry to an even higher level). He poured his genius into quartets, sonatas, symphonies, etc.; as to style, his work reflected the rococo baroque flourishing during his lifetime. What I am implying is that to be attached, related, committed —call it what you like—to ideas, people and our time, does not mean a loss of freedom. No, on the contrary, it is only through these connections that we can grow and flourish. Weston’s original interpretation of nature did not come out of a mind “free” from a love of nature, but because of it. Strand, because he works in the tradition of Humanist Realism, does not lose stature but gains it because of this connection. Not only would it be impossible for the perfectly “free” photographer to exist; but assuming he did, then he would have, quite literally, nothing to say.

Let’s take a photographer in 1973 who “freely” decides to place opaque objects on a piece of enlarging paper in the darkroom. Assuming the results are original and highly successful, he still will be making photograms, a style of photography highly developed by John Heartfield and Moholy-Nagy in the 30’s. Even if he never knew of their work, he still would be subject to the same influences they underwent. The result? He unknowingly makes photograms. This is because the talented photographer is simultaneously both a unique individual and a product of our time. May it always be so.

I have dealt at some length with tradition and interrelation of the arts because unless photographers get rid of the serious prejudice against them, we cannot appreciate the importance of Humanist Realism, one of the great highroads in photography.

When we say Realism, it is generally assumed that we are referring to a sharp picture, full of tonalities and detail; yet this is only one aspect of Realism. A photograph that gives us an accurate account of what is seen may be a good document, but it cannot be called art unless there is a significant contribution on the part of the photographer. Without it, the print degenerates from Realism into an example of Naturalism, a movement that deals more with the social environment and the totally subordinated relation of human beings to it, and is marked by meticulous attention to detail. A photograph which merely records, which does not give us the subjective interpretation of the photographer, is valueless as a creative statement. Often the photographer will organize his photograph effectively, but instead of depending on seeing in an original, penetrating way, he will adopt a standard composition, a way of seeing discovered in the works of previous photographers. This lifeless cop-out — an academic dependency on standard ways of seeing that have already been safely accepted — is called Formalism. I believe some of the work of Ansel Adams is typical of this academic tendency. Although on a high technical order, the results often are not seen in a sufficiently original way (I’m not talking of his best work, which has undeniable stature).

We photographers have to stop being provincial when it comes to understanding the broad movements of art, those running through history and at work today! This makes me think of a recent photography editorial concerned with whether there was really a battle of ideas and different approaches in photography. Yes, there is, but it is also part of a very real struggle taking place in the rest of the arts.

The main war is between Modernism, which places almost all emphasis on the artist’s feelings and makes reality a secondary matter (in painting,

Cubism, Dadism; and in photography, in the form of photo-distortions, etc.) and Realism, which considers the artist’s main job to be the interpretation of reality, with man as the central concern. What makes this ideological battle particularly complex is that a painter or photographer can show extraordinary vitality, talent and originality, say, in his or her photo-montages, so that someone in the opposite camp would be unjust to say that this work is without value because it is not in the Realist tradition!

We photographers have for so long been artificially isolated from the rest of the art world that in spite of the large degree of present day acceptance, we still maintain a self-imposed exile. Unless we get rid of this serious weakness, photography will not continue to flourish as a major art medium but, with barely a whimper, it will eventually wither away under a vast pile of pathetically sterile prints.